Fast food companies are having a rough couple of years. The bad economy took a toll on revenues for almost every major chain. Books like Fast Food Nation and the documentariesSuper Size Me and Food, Inc. have surely been a P.R. nightmare. The recent health reform legislation includes a federal mandate for all chain restaurants to post nutritional information for regular menu items in highly visible spots on the menuboard. (Fun fact: I heard a story on NPR that Starbucks customers had "sticker shock" after learning that their beloved Frappucino had well over 500 calories. In response, Starbucks switched the recipe from whole milk to 2%.)

Rough, right? Well, the hits just keep on coming. Apparently, the advocacy group Corporate Accountability International has called for McDonald's to retire their cartoon spokesclown Ronald McDonald. They say Ronald is a marketing ploy to get kids to eat unhealthy food - and in light of the childhood obesity epidemic, it's unethical for McDonald's to continue to use him to sell Happy Meals. The group held a retirement party in McDonald's homestate of Illinois, and sent "Happy Retirement" cards to McDonald's restaurants all around Chicago.

I wouldn't take this group's efforts too lightly - CAI is kind of a big deal. They're the ones who stomped cigarette spokes-ungulus Joe Camel out of the advertising world. And even though many first believed that a cartoon was harmless, the public ended up siding with CAI's anti-Joe stance. Most now agree that a company that uses a kid-friendly cartoon as a marketing mascot is, intentionally or unintentionally, marketing their products to children. And marketing to children is a real ethical minefield.

So is Ronald McDonald on the same playing field as that malicious dromedary Joe?

Economically, yes. I just read a study that said the national health costs of obesity are about the same as the national health costs of smoking - both hovering around $50 billion per year in medical expenditures.

Magnitudinally, yes. For children between the ages of 2 and 19, 17% are obese. For youth ages 11 to 19, 9% are "established" smokers.

When you really think about it, the advocacy group CAI isn't making a real stretch here. Like cigarettes, fast food causes loads of downstream health costs; obesity is much more prevalent than youth smoking; and on top of that, like nicotine, fast food is addictive. Many people say, "One happy meal isn't going to kill you." Well, one cigarette isn't either. It's the fact that people who regularly consume fast food are less able to control their urge to eat (much like people who regularly use cigarettes can't control their urge to smoke). And this is what worries Corporate Accountability International.

McDonald's counters these arguments with two key points. One, Ronald is the spokesperson for the Ronald McDonald House, a very active charity organization. They don't want to lose that branded imagery, which makes sense. Two, they say Ronald is, in fact, an advocate for making good choices and for being physically active and for having good meals with family. (I think this second argument is just one of those things spokespeople say because there's no way to refute this. Yeah, in '05 they "slimmed down" Ronald to say he promotes an active lifestyle. But I'm not sure he could have possibly achieved this on a McDonald's diet alone ... he had to have been cheating on his Big Macs with a Subway sandwich.)

I don't think McDonald's has to send poor Ron off to retirement. I think they just need to use him more as a role model for children to make smart choices - and that means making Happy Meals that are actually nutritious. Apples instead of fries. Grilled chicken sandwiches instead of processed chicken nuggets. Milk - plain milk, not flavored and loaded with sugar - instead of soda. Let Ronald show how much he loves vegetables.

CAI has a point that I think we should make sure McDonald's takes seriously. The analogy between the health effects of the cigarettes Joe Camel peddled and the junk that Ronald sells is hard to deny. Sure, keep Ronald around, but make him serve as a role model for making healthy eating choices. The childhood obesity epidemic is only going to continue to grow if big players like McDonald's don't start thinking creatively about how to change the food environment for consumers and their Happy Mealers.

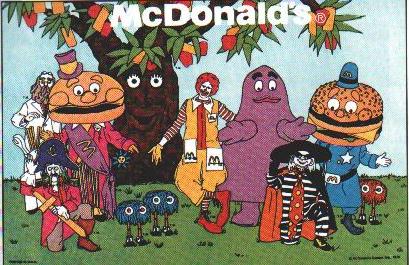

(Well hey, if nothing else, at least we can sleep soundly knowing that they retired the posse from McDonaldland years ago. I'm not sleeping better because of the lessened threat to childhood obesity - I'm sleeping better because these characters are creeeeepy. *Shudder*)